-

AHS Scam – P3 Capital Partners – Horners

Key player in the AHS scam is Doug Horner. He’s the Former Minister of Finance of Alberta who runs P3 Capital Partners Incorporated. Doug Horner is the father of Alberta’s current minister of finance, Nate Horner. After being incorporated by Sam Mraiche’s accountant Sam Jaber in February 2020, Alberta Surgical Group Ltd. (ASG) lobbied the…

-

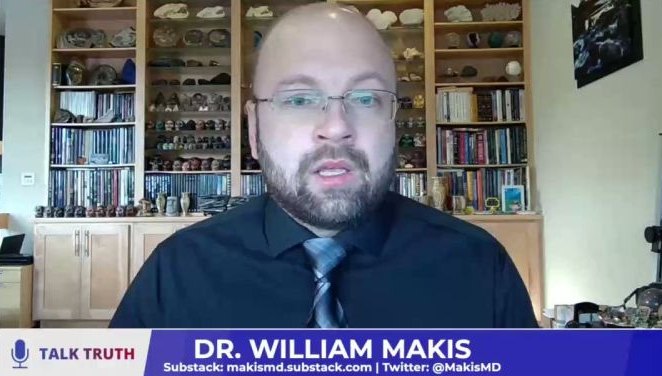

‘Dr’ William (Viliam) Makis – update

Cartoonist Scott Adams @ScottAdamsSays recently died after a battle with prostate cancer. The asshole William (Viliam) Makis slagged him for not following his high volume, high cost ‘protocol’. The fact was the dying Scott Adams took Makis vet deworming drugs for his cancer and not surprising they did absolutely nothing. William (Viliam) Makis is a…

-

Alberta Surgical Group – ASG – Sam Mraiche

Acute Care Alberta announced December 7, 2025 it had extended its contract for another year with Alberta Surgical Group. (ASG) Key owners/stakeholders include D’Arcy Durand, Leslie Scheelar, Kenneth Hawkins (khawkins@ualberta.ca), and Sam Mraiche. A new $34m one-year contract runs from Nov. 1, 2025 until Oct. 31, 2026 to provide about 4,000 orthopedic surgeries. Part of…

-

Kelowna mayor Tom Dyas – Denciti steal

A steal in the tens of millions is underway in Kelowna. City staff is telling reporters that its a done deal and “is expected to be finalized on March 30.” This declaration despite the rezoning requiring a council vote. The Kelowna Springs/Denciti steal is the brainchild of Kelowna Mayor Tom Dyas. In 2022 Dyas made…

-

Carlos Jesus Raygozaparedes

This space did a Superior Court of Orange County dive (File – 22NF0710) and that appears to show Sinaloa operative and former Sandher janitor Carlos Jesus Raygozaparedes pled guilty and bought himself a total of 19 years in jail (6 years concurrent). His lawyer was Douglas L. Lobato Raygozaparedes Jesus Carlos 22NF0710 Felony Mar 21,…

-

Métis Government Judicial Tribunal

asandmaier@metis.org “The Judicial Tribunal is an impartial body of the Judicial Branch of the Otipemisiwak Métis Government. Its members act faithfully and impartially exercise their duties under the Constitution and Otipemisiwak Métis Government laws …” Shea Taylor, John Phillips, Andrea Sandmaier, Lionel Chartrand, Arlan Delisle. There is a very basic, very fundamental problem. The Métis…

-

Hassan Khalil Sam Mraiche – update XI

Bennett Jones LLP is the Calgary-based law firm hired to defend the Alberta government against Ms. Mentzelopoulos’s claims. Munaf Mohamed (mohamedm@bennettjones.com) is the taxpayer funded parasite liartard. Neuman Thompson, a labor and employment law firm represents Alberta Health Services. (AHS) Parasites for AHS are Craig W. Neuman (cneuman@ntlaw.ca), and Chantel T. Kassongo. (ckassongo@ntlaw.ca) A GoFundMe…

-

Bryan Ward – Sam Mraiche liartard

Most shameless and crooked (and under qualified) of all Sam Mraiche liartards is Sherwood Park lawyer Bryan Ward. bryan@park-law.ca Bryan Ward bragged online about starting a law firm with his buddy Craig Floden in 2018. The name of the firm was initially named Floden-Ward LLP but now it is stripped of Ward’s namesake and remains…

-

Hassin Khalil Sam Mraiche – roots

Hassin Khalil Sam Mraiche was born in Edmonton in 1979 to immigrant parents. The earliest public records concerning Mraiche date back to 1998. Six days after his 19th birthday, he was busted for credit card fraud. When he was 21, he went bankrupt. He racked up more than $100k in debt with multiple banks and…

-

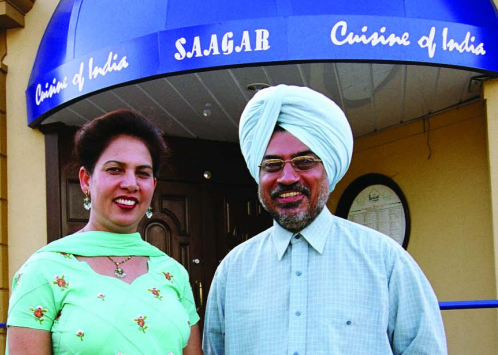

Prabtaj Singh Sandher – 4502 Pyman Road

The Sandher Crime Family are being nailed for another illegal creek diversion in Lumby. A violation notice was issued December 19, the 2nd after one was issued in August. The Sandher Crime Family are stealing Crown water again, and give no fuk, again. Here. Gurtaj Singh Sandher ________________________________________________ Mike’s Creek was diverted illegally into an…

-

RCMP Grant Shade, wife Katrina Shade nailed for fraud on Piikani First Nation

Const. Grant Shade, 42, and Katrina Shade, 40, both of Pincher Creek, Alberta, were charged with fraud over $5,000 and theft over $5,000. Katrina Shade had worked for Piikani Resource Development Ltd since 2015. In March the Piikani First Nation retained an independent forensic investigator. That revealed significant financial irregularities at PRDL over a long…

-

The Panama connection – Hassan Khalil Sam Mraiche

Hassan Khalil Sam Mraiche set up a Panamanian company in 2014. Names apparently associated as directors are Jesus Enrique Mendoza Guerra and Joseph Salame. In January 2025, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith took a two-week vacation to her Panama property, which was seen as poorly timed. Her trip included meetings with Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago, which…

-

Jolene Johnson – West Point Investigations

The next court appearance for filthy dirty PI Jolene Johnson (Diana Leigh Holden) is January 19. Considering she was charged years ago, her time is surely running out. One may complain about criminal licensed ‘PIs’ at (info@piabc.ca) and (securitycompliance@gov.bc.ca) and (SPDCompliance@gov.bc.ca) ___________________________________ Jolene Johnson has Jessica Simpson/Jonathan Yaniv living in her head. https://x.com/BarbaraDoduk/status/2009813801235841441 Jolene Johnson…

-

Athana Mentzelopoulos – Hansard the cat

Speaking publicly about the harassment campaign of David Wallace for the first time, former AHS chief Athana Mentzelopoulos said Wallace has repeatedly attacked her reputation, called her “disgusting names” and said people “were coming to my house.” Mentzelopoulos told The Globe and Mail she was disturbed that the Premier had previously used a talking point…

-

Killer Prabtaj Singh Sandher talks trash with Mohini Singh

Kelowna City councilor Mohini Singh (Ubhi) had a chit chat with the killer of Donny Lyons and alpha level drug producer Prabtaj Singh Sandher. Donny Lyons was murdered June 15, 2024. Prime suspects are Prabtaj Singh Sandher and Gurtaj Singh Sandher. 100% a pity party about how hard done by the Sandher Crime Family is,…